Cinema bolognese

Tuesday | July 3, 2007 open printable version

open printable version

Cinema Ritrovato, a festival of rediscovered and restored films, is now in its twenty-first year. We visited its two previous installments, and we found it one of the most hugely enjoyable festivals on the calendar. Where else can you see films from 1907, Richard Fleischer’s Violent Saturday (1955), and a tribute to Ben Gazzara in a single week? Then there are the nightly screenings on the Piazza Maggiore, which attract hundreds of locals. The city plays host magnificently, with plenty of fine restaurants and perpetually cheerful people.

Mounting hundreds of screenings and panels is an enormous effort, but Gianluca Farinelli, Guy Borlée, Peter von Bagh, and all their colleagues have made it look easy. (The word sprezzatura comes to mind.) Here are our impressions from the first half of the event.

The home base is the Cineteca di Bologna, the local film archive. It’s located in a wide, quiet courtyard. It houses a large library and meeting rooms, along with two cinemas. During the festival, the Lumiere 1 auditorium specializes in silent screenings with piano accompaniment, while Lumiere 2 presents sound films. Widescreen titles and big events are reserved for the Arlecchino, a big, comfortable commercial theatre built in the era of roadshows and CinemaScope.

Organizing such a mixed program is more difficult in certain ways than presenting an event involving contemporary films, which are moving through the festival circuit already. Ritrovato must find good prints of titles that fit the year’s themes and also coordinate the ongoing efforts of archives that are restoring films.

A good example is a remarkable project overseen by Alexander Horwath of the Austrian Film Museum. One of the most famous lost films in US history is Josef von Sternberg’s 1929 movie The Case of Lena Smith. In 2003, Japanese scholar Komatsu Hiroshi found a fragment, in very good condition, in China. On the basis of this, Horwath and his collaborators created a wonderful book that reconstructs the film. It includes a detailed shot breakdown (based on one published in Japan during the film’s release), along with gorgeous stills, script extracts, summaries of critical reception in various countries, and essays about the film’s place in history.

The fragment, previously screened at the Giornate del Cinema Muto last fall, was tantalizing. Lena and her friend Pepi are in the Prater, Vienna’s dazzling amusement park, and they are eyed by two young officers. The women watch some of the sideshow entertainments before darting away, the officers in pursuit. Several of the shots evoke the heady atmosphere of the park, with prismatic, superimposed images of the sideshow attractions and—typical von Sternberg—a spinning ride providing pulsating visions of the crowd.

In his panel presentation, Horwath stressed that the book couldn’t have been done without the cooperation of researchers around the world. The multilingual volume is to be made available in the UK and the US in 2008. It is a splendid example of what archives and scholars can accomplish working together, with festivals like Cinema Ritrovato providing a forum for rediscoveries. The book is available already at the archive’s website and will be distributed later this year by Wallflower in the UK and Columbia University Press in North America. (DB)

In his panel presentation, Horwath stressed that the book couldn’t have been done without the cooperation of researchers around the world. The multilingual volume is to be made available in the UK and the US in 2008. It is a splendid example of what archives and scholars can accomplish working together, with festivals like Cinema Ritrovato providing a forum for rediscoveries. The book is available already at the archive’s website and will be distributed later this year by Wallflower in the UK and Columbia University Press in North America. (DB)

One of the threads of this year’s festival is the early US career of Michael Curtiz. The Strange Love of Molly Louvain (1932) is an energetic Warners crook melodrama. Starring Ann Dvorak and the ever-annoying Lee Tracy, the film displays Curtiz’s characteristically staccato direction. The scenes with hard-bitten reporters use overlapping dialogue in a manner that prefigures His Girl Friday. Rarer was The Third Degree (1926), an early instance of Europe’s “International Style” infiltrating Hollywood. For his first Warners project, Curtiz fills an implausible mother-daughter melodrama with cloudy superimpositions, canted angles, florid tracking shots, oddball angles, extreme close-ups, and frantic montages played with prismatic lenses. Richard Koszarski gave an amusing and helpful introduction. (DB)

One attractive constant of the Ritrovato is a series of short films from 100 years ago. Thus when we first attended in 2005, there were groups of shorts from 1905. As we progress through the early years of the current century, we go in parallel through the early years of the previous one. Each day one or two small groups of 1907 films have been shown, grouped by country or genre. These included some familiar items, like the poignant Le Bagne des gosses (“Children’s Prison,” Pathé) and the amusing British chase film, That Fatal Sneeze (directed by Lewis Fitzhamon). I have run across references to early Westerns made in Europe but had not seen any from this early period. Les Apaches du Far-West (produced by Pathé) is as unauthentic as one might predict, with the cowboys riding on English-style saddles and the shoot-outs with the Apaches taking place in bucolic fields and woods that are clearly in France, not the West. (KT)

A major new initiative for international film preservation was announced in May at the Cannes Film Festival. The World Cinema Foundation was founded by Martin Scorsese, and its advisory board contains such major filmmakers as Abbas Kiarostami, Elia Suleiman, Walter Salles, and Wim Wenders. The goal is to restore films made in nations that lack the archival facilities to do so locally.

The Moroccan Transes (El Hal, 1981), directed by Ahmed El Maanouni, is the new foundation’s first restoration, and it was introduced by the director and by its producer, Izza Genini. The titles crediting Giorgio Armani, Cartier, and Qatar Airlines as sponsors raised some surprised laughter in the audience, but if Scorsese and his colleagues can draw funding from such sources into film restoration, all the better. Transes is partly a concert film and partly a history of a band that became popular in the 1970s by expressing young people’s frustrations and rebelliousness. The big concert that begins and ends the film is exhilarating in its depiction of the crowd’s enthusiasm—but chilling as well as soldiers patrol the audience and occasionally suppress the more demonstrative spectators. (KT)

Another major theme is the ever-popular star Asta Nielsen. Again, items familiar from other retrospectives are mixed with new discoveries. Karola Gramann has curated the series and plans to restore other Nielsen films, either new discoveries or better prints of familiar films. Zapatas Bande (1913-14), for example, existed before, but now a color print has been made based on tinting notations on an existing black-and-white copy. It’s a slight item, a casual tale of filmmakers getting into trouble while shooting an adventure movie, but it allows Nielsen to get away from her usual melodramas and display her range as a comic actor. (KT)

Another major theme is the ever-popular star Asta Nielsen. Again, items familiar from other retrospectives are mixed with new discoveries. Karola Gramann has curated the series and plans to restore other Nielsen films, either new discoveries or better prints of familiar films. Zapatas Bande (1913-14), for example, existed before, but now a color print has been made based on tinting notations on an existing black-and-white copy. It’s a slight item, a casual tale of filmmakers getting into trouble while shooting an adventure movie, but it allows Nielsen to get away from her usual melodramas and display her range as a comic actor. (KT)

Our first visit to Italy for a film festival was in 1986, when Le Gionate del Cinema Muto, in Pordenone, presented a vast retrospective of Scandinavian cinema from the pre-1919 era. One of the major revelations was that alongside Mauritz Stiller and Victor Sjöström, there was a third great Swedish director during the silent era, Georg af Klerker. The event also brought home to the audience one of the great tragedies of cinema history, the loss of many of Stiller’s and Sjöström’s films in an archive fire in the 1940s.

Every now and then, another film by one of these masters surfaces. This year the Ritrovato festival showed Madame de Thèbes, a 1915 Stiller film. As too often happens, the surviving copy, a French release print discovered by Lobster Films, was incomplete. The Svenska Filminstitutet has filled it out by inserting still shots created from copyright frames deposited at the Library of Congress and by replicating the original Swedish intertitles and letters. The result, full of sumptuous decor and extravagant plot twists, gives as good an approximation of the original as is now possible. It’s one more indication that the 1910s Swedish cinema was one of the glories of the silent era. (KT)

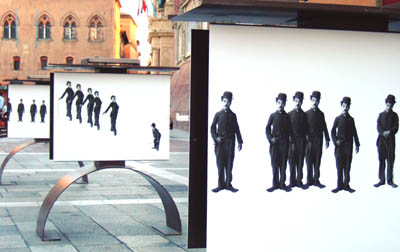

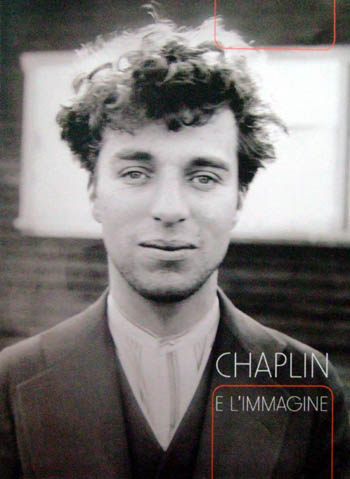

The festival has a close relation with the Charlie Chaplin estate; this is the place to come for the latest in Chaplin restorations and scholarship. Every year the festival mounts a tribute, including a superbly designed book on some aspect of Chaplin’s career. This year’s volume is a collection of rarely seen pictures, and its cover carries one of the most melancholy and haunting portraits of Charlie I’ve ever seen (up top).

The first big event of the festival was a screening in the city’s Teatro Communale, an overpowering opera house. It was a fitting venue for The Idle Class (1921) and The Kid (1921), accompanied by orchestra. The prints were pristine, shown in a nearly square ratio. The version of The Kid was based on Chaplin’s 1971 rerelease, since that represents his final thoughts, but the Bologna gang generously tacked on the material that Chaplin chopped out—all scenes with Edna Purviance, playing the unwed mother who abandons her baby. These scenes include her uneasy meeting her old lover years after she’s achieved success. The plot turn and the regretful tone seemed to me to look forward to A Woman of Paris. This version, along with the deleted scenes, is available on the MK2 DVD release.

The first big event of the festival was a screening in the city’s Teatro Communale, an overpowering opera house. It was a fitting venue for The Idle Class (1921) and The Kid (1921), accompanied by orchestra. The prints were pristine, shown in a nearly square ratio. The version of The Kid was based on Chaplin’s 1971 rerelease, since that represents his final thoughts, but the Bologna gang generously tacked on the material that Chaplin chopped out—all scenes with Edna Purviance, playing the unwed mother who abandons her baby. These scenes include her uneasy meeting her old lover years after she’s achieved success. The plot turn and the regretful tone seemed to me to look forward to A Woman of Paris. This version, along with the deleted scenes, is available on the MK2 DVD release.

The score was by Timothy Brock, who also conducted. On the following day Brock gave an enlightening seminar on how he based his scores on original themes that Chaplin came up with. Chaplin was in the habit of working and reworking tunes at the piano, and many of his efforts were recorded. The recordings came to light three years ago, and Brock was able to integrate the tunes into his scores—sometimes linking five or six in a single passage. (DB)

The score was by Timothy Brock, who also conducted. On the following day Brock gave an enlightening seminar on how he based his scores on original themes that Chaplin came up with. Chaplin was in the habit of working and reworking tunes at the piano, and many of his efforts were recorded. The recordings came to light three years ago, and Brock was able to integrate the tunes into his scores—sometimes linking five or six in a single passage. (DB)

A cloud was cast over our visit by the news of the death of Edward Yang (Yang Dechang). We admired his films and discussed them in Film History: An Introduction and my Figures Traced in Light. Edward was a likeable, tough-minded fellow. His films explored the effects of urbanization and politics on everyday life in Taiwan. He made his breakthrough to a broad international audience with Yi Yi (2000), but his other films, particularly Taipei Story (1985), The Terrorizers (1986), and A Brighter Summer Day (1991) are to me even more important. It’s a great loss that these aren’t easily available on DVD. When I get back to Madison and have access to pictures from my encounter with Edward in Kyoto in 1997, I hope to write a more adequate tribute. (DB)